Other Recent Articles

Fathers of French Cuisine – Escoffier

Unlike his predecessors, Auguste Escoffier cooked for the public. Not privately for royalty and high society as was the case for Antoine Careme. And to a lesser extent La Varenne. But building on the foundations that La Varenne and Careme established, Escoffier donated the final refinements to French Cuisine as we know it today.

Escoffier’s career began at the age of thirteen at his Uncle’s restaurant in Nice. Here he received no favors as the nephew of the boss. And, as a result benefitted from a strenuous apprenticeship that he would later appreciate and, of course, build upon.

The chance to construct what was to become one of the most high profile careers in the History of French Cuisine came when his talent caught the eye of a Parisien resturanteur, who invited Escoffier to join his team. After three years, Escoffier, at the ripe old age of twenty one, became head chef of Le Petite Moulin Rouge. One of the finest restaurants in Paris.

Escoffier’s next “career move” was’nt one of his choosing. At the outset of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, he was called up to serve – at the stove. Although for some chefs this might have seemed a step down the ladder of culinary advancement, it inspired Escoffier to study the techniques for canning meats, vegetables and sauces. As the military required meals that would preserve well.

After the war, Escoffier returned to Paris and his position as head chef at Le Petite Moulin Rouge, remaining until 1878. Subsequently, he held a number of similar high profile positions in Paris, Monte Carlo and Switzerland. It was in Lucerne that Escoffier met a former hotel groom who was to supercharge his career. Cesar Ritz.

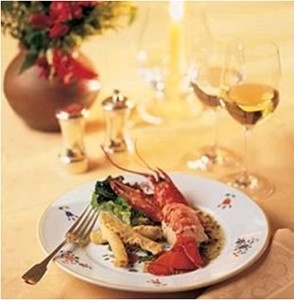

Basically, Ritz had the hotels. And in each one – Escoffier ran the kitchen show. At the Ritz in Paris. At the Savoy and the Carleton in London. Where the clients included such luminaries as the Prince of Wales. It was here also that Escoffier would create a new dessert in honor of the Australian singer Nellie Melba. A little trifle called : “Peach Melba.”

During his twenty year tenure at the Carleton’s stove, Escoffier created some of his most famous dishes. Among them “Chaud-Froid Jeanette” and “Cuisses de Nymphe Aurore” – a frog’s legs dish named after the Prince of Wales.

It was during this time that Escoffier would further refine the contributions of Careme and La Varenne. Simplifying Careme’s complex approach to cooking, and abandonding excessive garnishes, heavy sauces and elaborate preparations.

In addition to streamlining and simplifying French Cusine, Escoffier also instituted similar reforms in the kitchen itself. Better working standards were his first accomplishment. Obviously attracting a better quality of kitchen help. Swearing and alchohol were forbidden. Hygienic standards were increased. And the French Chef introduced the current “brigade” system. Where each chef is responsible for a certain section of the kitchen.

When Ritz had a nervous breakdown in 1901, and their partnership effectively ended, Escoffier turned his attention to recording his recipies and techniques. He produced five books. His first “Le Guide Culinaire” quickly began, and today remains, the Chef’s “Bible.”

Although he’d planned to retire in 1919, the year he turned 73, Escoffier was persuaded by the widow of his former boss at Le Petite Moulin Rouge to help with the administration of the Hermitage Hotel in Monte Carlo. Later, this aged, but obviously inhaustabile dynamo also assisted in developing the Riviera Hotel there.

In addition to his books and cooking for the privileged, Escoffier also organized programs to feed the hungry and give financial assistance to retired chefs.

Auguste Escoffier, the simple country boy from Villeneuve-Loubet who became the world’s second celebrity chef(after Careme) died in Monte Carlo in 1935, at the age of 89. Leaving a legacy of 10,000 recipies, five books, and constant inspiration to all who appreciate French Cuisine.

THROW ME A BONE HERE, PEOPLE!

What are ya thinkin’?

Fathers of French Cuisine – Careme

He was abandoned on a doorstep at the height of the French Revolution. Though seemingly without prospects or hope, Antonin Careme would grow up to be called “The King of Chefs and “The Chef to Kings.”

Careme’s incredible good fortune, some might say “destiny”, began with the doorstep on which he landed. It belonged to a Monsieur Sylvain Bailly, a famous patissier, with a shop near the Palais Royal, who gave the nine year old Careme bed and board in exchange for general kitchen work. More than just a kind soul, Sylvain Bailly, was in, fact, Careme’s first mentor. Encouraging his young helper to advance and learn.

This combination of encouragement and Careme’s talent, culminated in the opening of Careme’s own pastry shop – at the ripe old age of eighteen. On his own, Antonin Careme was “on a roll”. Owing to the fact that pastry, particularly innovative creations, were Paris’ flavour of the moment.

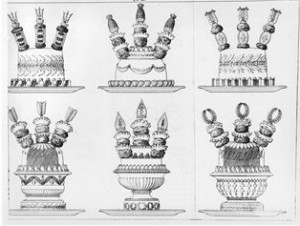

And Careme’s creations were innovation on steroids. In fact, Careme was essentially a sculptor, using icing sugar, nougat and marizan as his materials. Inspired by architecture and famous monuments, Careme created and re-created pyramids, helmets, and waterfalls. Never intending that that they should be actually be eaten.

Happily Parisian Society was “eating up” Careme. He was truly the “Big Man on Campus.” And, his campus to boot! Clearly the teen-age Careme was the toast of Paris. Whether or not that was the height of his ambition, is open to speculation. No matter. Young Antonin was about to have, as the saying goes – “greatness thrust upon him.”

Careme’s talent and accomplishments had come to the attention of the man who would become his second, last, and most influential mentor. Prince Tallyrand. The consummate diplomat who survived all that era’s political upheavals. Tallyrand was, or at least considered himself to be, a gourmet. He invited Careme to be his Chef. On the condition that he prepare a year’s worth of menu’s without repeating himself. Dare I say – “a piece of cake” for Monsieur C?

His association with Tallyrand elevated Careme to the highest strata of European Society and Royalty. After Napolean met his Waterloo, Careme decamped for England, where he cooked for the Prince Regent. Later to become King George the Fourth. His culinary carousel continued with an invitation to St. Petersburg.(The one in Russia folks.) Although, for whatever reason, he never actually got to cook for the Tsar.(Preparing for the next revolution?) So – back to Paris. Firing up his stove for banker J.M. Rothschild.

Without a doubt – Antonin Careme was the first “Celebrity chef.” But it is his contributions to the art of French Cuisine that has (justly) earned him the title : “King of Chefs.”

Here they are:

1.His book on pastry – Le Patissier Royal Parisien.

Only the third book of that time to be devoted exclusively to the patissier’s art. And the first one to have extensive engraved plates. Careme’s designs for these engravings resemble more elaborate architectural constructions, than pictures of food.

2.His book on Cuisine – L’art de la Cuisine Francaise au XIXe siecle. Here he extends his wild, wacky, weird, and way out imagination to the preparation and presentation of meat, poulty and seafood.

But, he also did some more serious stuff – like giving future chefs the ability to create an almost unlimited variety of dishes by utilizing a series of basic prepartions Careme developed. He also classified all sauces into groups, based on four main sauces.

Careme is credited with ending the practice of serving all the dishes at once(“Service a la Francaise”), and replacing it with the one we know today. (“Service a la Russe”) Where the grub arrives in the order on the menu. Careme also gets a “tip o’ the hat” for inventing it. The chef’s hat(toque) that is.

Sorry to say – no happy ending for Antonin Careme. After blazing across the culinary heavens, rubbing shoulders with the high and the mighty of nineteenth century Europe, and leaving an enduring legacy – he joined his pal La Varenne at that big stove in the sky – at the tender age of forty eight.

Better to burn out than fade away? (as Neil Young would, and did, say)

THROW ME A BONE HERE, PEOPLE!

What are ya thinkin’?

Fathers of French Cuisine – La Varenne

While it’s tempting to call him the “Father” of French Cusine, in reality, Francois Pierre de la Varenne, was one of three Fathers to the great art. The other two being Antoine Careme and Auguste Escoffier.

But it was La Varenne, who was first out of the gate. A rebel. An insurgent. Tilting against the established culinary windmills. Which, in 17th Century France were heavily rotated by the Italian cuisine of the Middle Ages. Favoring heavy doses of pungent spices. This wasn’t on the menu for a guy whose motto was : “Health, moderation and refinement.”

Thus, Francois Pierre deep-sixed the cinammon, cloves, myrhh and other goodies from the three wise men, and brought on the parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme. His (for those) times “revolutionary” idea being that the natural flavor of the ingredients should dominate, and not be smothered by and in heavy sauces.

As you would expect, vegetables now took the pole position, with meat bringing up the rear. And, ever the ground breaker , he introduced an exotic meat from the far away lands to his recipies- a thing called – Turkey.

Cleary on a roll, La Varenne replaced crumbled bread for stock with roux, introduced the first bisque and béchamel, and began using egg whites for clarification. He’s also credited with an early form of Hollandaise sauce.

Not content with just all this innovation and creativity, Francoise Pierre put quill to paper, and produced “Le Cuisinier Francois.” Regarded as the founding text of modern French Cuisine. In it, he systematically detailed, according to rules and principals, the considerable advances that had been made in 17th Century French Cuisine.

Tipping his toque to one of his earlier employers, the Marquis d’Uxcelles, La Varenne immortalized him by naming his creation of finely minced mushrooms seasoned with herbs and shallots – “Duxelles.”

Francois Pierre, however, unlike Duxelles, did not get to be immortal.

He went to that big kitchen in the sky at the age of 63. (Old for the 17th Century.) But his writings and recipies, copied, printed, re-printed continue to circulate, and most importantly – inspire.

Not a bad legacy, eh wot?

THROW ME A BONE HERE, PEOPLE!

What are ya thinkin’?